After praising them yesterday, I’m afraid I’m going to say some things members of the new Coalition for Columbia’s Downtown aren’t going to like. First, the good:

“There’s nothing for low-income housing” in the county’s plan for redeveloping downtown Columbia, said Alan Klein, head of the newly formed Coalition for Columbia’s Downtown.

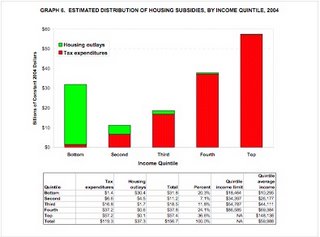

…The Department of Planning and Zoning proposed setting aside 10 percent of units for moderate-income housing and 5 percent for middle-income units, according to the draft plan. Klein said that accounts for those making $50,000 to $100,000 a year and overlooks those who make less.

The group proposed setting aside at least 20 percent of all units for moderate- and low-income housing.

“We simply will not accept the fact that its impossible to have low-income housing in Columbia,” said Del. Liz Bobo, D-District 12B, who spoke at the group’s gathering Monday in Columbia.

Yes, yes, yes. It is not impossible to have housing for those making less than $50,000 a year. In fact, it is essential, despite

despicable characterizations to the contrary.

The idea of a jobs-housing balance is one that has gained considerable steam over the past couple years, and it calls for, essentially, a housing stock that is tailored to the income profile of our workforce.

Philosophicaly, the foundation of the concept is that everyone should be able to live near where they work. Pragmatically, reducing the distance between home and work offers many benefits for residents and the community at large – namely, lower traffic volume, increased viability of local transit, decreased pollution, more quality time with families, stronger civic connections, and more.

So, we pretty much agree that affordable housing is a desireable in downtown Columbia. But here’s where we part ways: “The group also advocates fewer residential units to be built downtown — 1,600 rather than the planned 5,500…”

No, no, no. If affordable housing is really such an overriding concern, calling for a 780-unit reduction in the potential number of affordable units doesn’t seem like the best decision. Under their ideal scenario, Town Center would produce over the course of 30 years 320 affordable units, less than 11 each year. Which hardly seems worth it considering the county is faced with an

almost 30,000 unit shortage of affordable housing.

I’m not suggesting that Town Center is the panacea for our affordable housing situation, but it is an area with significant development potential where real progress could be made -- and not just on affordable housing, but on many of our other deficiencies (lack of decent transit, cultural amenities,

small businesses, etc.).

Because of the vast potential we have in Town Center, I’m hesitant to support proposals that tie its legs before it's had a chance to get out of the gate.

Rather than focus on the numbers -- which

as I clumsily said in the past are just abstractions at this point -- we should focus on the equation for the numbers.

Trying to plan in detail the next 30 years of development for Town Center is full of pitfalls, not to mention the fact that such an exercise completely devalues the preferences of future Columbians. Instead of deciding on every last detail now, we should focus on the short term specifics and keep the long term discussion focused on guiding principles.

The real-world manifestation of this idea is to create a visionary, overarching 30-year plan and develop a series of shorter-term, detailed oriented plans with, say, five- or ten-year time frames to implement this vision.

These shorter plans can house our limits, or, in my preferred scenario, they would include incentives and benchmarks to gauge our progress in meeting the longer-term goals -- like affordable housing, environmental quality, transit and infrastructure improvements. So, instead of prescribing the exact number of units to be built within each period, the plans could create a framework where the intensity of development is linked (within a reasonable extent) to the quality of development and the quality of amenities we receive. To make it fair for everyone, these incentives and benchmarks must carry the force of law.

Reward good behavior and good development with more density. Punish failure to meet stated benchmarks with density reductions. In short, create a market for quality development that actually captures the externalities -- both good and bad -- of growth and ascribes financial value to that which previously lacked it.