Another ignored study...

Anyone who has read this blog for a while or who knows me personally should be well aware that affordable housing is something I care about deeply.

Accordingly, I’ve been following the work of a county task force charged with addressing housing affordability in Howard County, a problem that many believe is growing. A story in today’s Sun offers a glimpse of some of the possible recommendations the committee will release in its final report, which is due by October 31.

• Permitting greater density, or the number of homes per acre. Developers have long insisted that skyrocketing land costs in the county make it economically infeasible to construct single-family homes for low- and middle-income earners.Also discussed is the idea of creating a community land trust – essentially a non-profit entity that buys land, the most expensive component in the cost of housing, and builds affordable units on its property. The buildings – not the land – are sold to qualified buyers, with contingencies to ensure the property is permanently affordable. It is one of the few solutions that offers sustainable affordability, although because of rising costs and diminishing supply of land, it may have limited success in Howard.

• Authorizing taller, multifamily buildings, which also results in higher density.

• Increasing public funds, perhaps by increasing the excise tax, that could be used in unison with developers to make construction of affordable-housing economically practical.

• Revamping zoning regulations, which many developers complain are cumbersome and result in undue delays and higher costs.

• Increasing the number of housing units that can be constructed annually. The county restricts that to about 1,700 a year, but Armiger said perhaps units designed for low- and middle-income earners should be above the regulated cap.

• Making "excess" public lands available for development.

Going back to the list of possible solutions, it’s pretty clear that some will be controversial -- in particular, those that relax development restrictions (building heights, density) and even, to an extent, those requiring greater public funding. Over the past few years, the approach with the most widespread support is that which requires developers to set aside a percentage of newly built units for moderate-income households. Not surprisingly, this is also the approach that requires the least amount of sacrifice and acquiescence from existing residents.

The task force, however, seemingly believes (and rightly so, I think) that set asides as described above are not sufficient to fully address the affordability problem. Therefore, they hope to match their beliefs with reality and gain a little political will at the same time.

The complexity of its work is underscored by the fact that it knows neither the scope of the problem today nor what it will be in the future, and by the admission that unanimity among the sharply diverse group might be impossible.Local affordable housing advocates have long maintained, largely via anecdote, that the affordability problem is real and growing. And, as stated above, the truth of the situation is not well known. But how hard can it be to show the problem exists?

Nonetheless, quantifying the need remains a goal, because without pinpointing the problem the hope of winning broad support for its recommendations becomes more difficult.

I spent a couple minutes today trolling the Census website and came up with a few charts that might shed some light on the situation (this is, pretty much, what I get paid for).

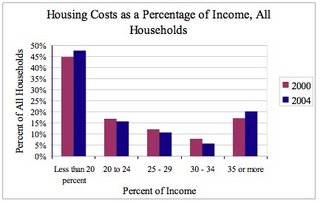

First, let’s look at housing costs as a percentage of income (keeping in mind that to qualify as “rent-burdened” in HUD’s terms or “house poor” in common parlance, you must pay more than 30 percent of your gross income towards housing).

For all households, we have this:

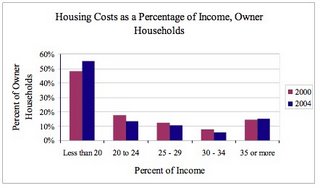

Interestingly, those paying 35 percent of more of their income towards housing increased at the same time those paying less than 20 percent did. Which is not as surprising when you look at these two charts, separating owner and renter households.

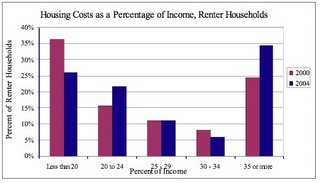

So, while the distribution remains basically the same for owners, except for the significant up tick in those paying less than 20 percent of income, the distribution for renters changed pretty dramatically – over a third of all renters now pay more than 35 percent of their income for housing, and the percentage of those paying less than 20 percent dropped by more than ten points.

So, while the distribution remains basically the same for owners, except for the significant up tick in those paying less than 20 percent of income, the distribution for renters changed pretty dramatically – over a third of all renters now pay more than 35 percent of their income for housing, and the percentage of those paying less than 20 percent dropped by more than ten points.In a county with considerably more owners than renters (71,577 to 25,684, respectively), it is not surprising that the trends were harder to distinguish when all households were combined into one chart.

Another factor to consider when looking at the chart for owners is that banks will not approve mortgages (for the most part) if your income doesn’t qualify, meaning it’s fairly unlikely that we would see large numbers of owners paying more than 35 percent of income towards housing.

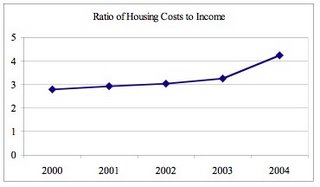

Of course, there are plenty of other charts one could make suggesting that there is a growing affordability problem. For instance, the ratio of median house value to median income:

(The current rule of thumb is that the cost of your house should roughly equal three times your annual income.)

So, after only a couple minutes, I’ve managed to create a series of charts that show a growing disparity between incomes and housing, the definition of an affordability problem. Just imagine what a paid government employee, doing this stuff five days a week, could accomplish.

However, it occurred to me while I was doing this that all the fancy charts and expensive studies in the world probably don’t matter. While a rigorous study demonstrating conclusively that the scope of the problem is large may increase political will to an extent, it will not create the groundswell of support needed to make affordable housing a top priority, let alone to “solve” the issue.

Either people care about affordable housing or they don’t.

As someone who can’t take two steps without falling under the gaze of Jim Rouse, I obviously care about affordable housing. True believers in the Columbia Idea care about affordable housing. Mushy bleeding heart-types and socialists care about affordable housing. But we all care about it regardless of if the problem is growing or shrinking or critical or whatever.

We believe that mixed income communities function best for everyone, that people should have a right to live near where they work, that your future should not be determined the ZIP Code you were born into. And to bolster our beliefs, we point to things like the 1949 Housing Act, which guaranteed a “decent home and suitable living environment for all Americans.”

That statement is often considered by people like me as part of the Bill of Rights: every American has a right to live in a good home.

What’s not guaranteed, and indeed overlooked by local advocates, is the fact that the location of this suitable living environment is left promised. To be sure, nobody wants poor kids growing up in concentrated poverty, but that doesn’t mean they want them growing up down the street either. And that’s their choice, whether you agree or not.

No amount of studies are going to convince everyone that affordable housing is an issue we need to address. As long as we have housing and job markets that stretch across multiple counties and jurisdictions, the will to create more affordable housing in one subset of the market – Howard County – while it’s readily available in other parts will likely never materialize.

So, even if the task force’s study shows low-income families being pushed out or burdened at an alarming (to my sensibilities, anyway) rate, the response from many, perhaps even the majority, will be: So what?

I still support efforts to better understanding the housing, income and jobs imbalance in our county, even if the stated goal for such a study makes it a fool’s errand.

4 comments:

You're right about the county program. It's generally a good way to keep a house permanetly affordable (as opposed to some programs where only the first buyer gets the house at an affordable price). The problem is, the county only has a handful of houses each year that it sells, and winners are chosen via a lottery, which is a pretty apt description of what getting one of these houses is like -- winning the lottery.

A major problem with all this is that making our existing stock of housing more affordable is impossible, absent a major macroeconomic disturbance. What's more, when we lose houses that are affordable to redevelopment (as in, all the trailer parks on the Rt. 1 corridor), no one seems to notice or care but the problem just gets that much worse.

You're right about the county program. It's generally a good way to keep a house permanetly affordable (as opposed to some programs where only the first buyer gets the house at an affordable price). The problem is, the county only has a handful of houses each year that it sells, and winners are chosen via a lottery, which is a pretty apt description of what getting one of these houses is like -- winning the lottery.

A major problem with all this is that making our existing stock of housing more af

Housing affordability is a problem I have more than a passing interest in as well. There some programs out there to subsidize multifamily housing for low income persons, such as the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, but I secretly wonder how much that really does for housing affordability overall. For sure it helps low income persons, but then the supply of housing is reduced for middle income folks, so how can you really say that the program is a net positive when it just puts upward pressure on housing prices for those folks earning just above low income? That same question can be raised for all government intervention in the housing market.

Housing affordability is really a symptom of a larger problem of poverty. Attempts to solve housing affordability problems are really hacking at the leaves and not the root. The affordability problem has been multiplied recently do to real estate prices (and thus rent) rising MUCH faster than wages. The good news is that the super hot real estate market appears to cooling off, so hopefully rents will drop as well.

Discussing pursuing more affordable housing and giving voice to proposals such as increasing density or making "excess" public lands available for development in the absence of any mention of environmental considerations certainly makes this discussion an incomplete treatment of the topic. There's no free lunch. If density increases and public lands are converted from habitable greenspace to development, then the environment loses.

There are, however, other solutions not mentioned here that I doubt will make their way into the final report.

° Putting the onus on developers to include a certain percentage of affordable housing in any new development over a certain number of units instead of any of the ways listed in your post which either put the onus on public resources, increasing taxes, or remove zoning safeguards against detrimental development.

° Stop running a federal deficit at the expense of future generations. This federal deficit results in a larger federal budget than would otherwise be. With a smaller, responsibly sane federal budget, economies elsewhere in the country would improve and the impetus to move to this area for jobs would ameliorate and housing costs would moderate on their own.

° Improve housing codes to require greater energy efficiency, thereby decreasing utility expenses, thereby increasing income available for mortgage payments.

° Improve mass transit, thereby reducing commuting costs, thereby increasing income available for mortgage payments. Add up your household's transportations costs (car payment, insurance, gas, and maintenance). Odds are it's many thousands of dollars per year. With effective mass transit, that could be halved.

° Improved mass transit would also allow better access to more affordable housing in surrounding areas and access to the job base here.

° Encourage more economical architecture. a geodesic home frame costs 30% less to construct than a rectilinear frame and also costs 30% less to heat and cool. This results in both a lower principal amount and more income to pay the mortgage.

Post a Comment